All the investors own all the assets. This is a tautology, but it has interesting implications. Most people (and institutions) own stocks and bonds that are very, very expensive. Since all the investors can't actually get rid of these, collectively, but only trade them around among themselves, most of the investors will experience the consequences of owning stocks and bonds that are very expensive, in whatever macro environment we may have in coming years, which might be pretty interesting.

Even if nothing very bad happened, and currencies remained sound, this does not promise very good investment results for the next decade. You can see the nominal investment return on a bond just by its yield-to-maturity. It is lower than it has ever been. The typical outcome for stocks, beginning from today's valuations in the U.S., is a decade or so of going sideways with some disgusting ups and downs. You would probably be better off in cash, just as you would have been better off in cash in 2000-2009; although nobody from Wall Street, during that time, ever breathed that such a thing was possible. Foreign stock markets, although cheaper, are not much better.

This is bad enough as it is, but I think we are in the early stages of a monetary event worldwide, that will probably result in 80%+ real losses in stocks, bonds and cash -- all three. This might play out over a period of 5-8 years. It is not some two-week catastrophe. This would be quite an experience for All the Investors who own All the Assets. The essence of this "monetary event" is a decline in all currencies worldwide. Of course, this would include a "decline in the dollar," but it would also include a decline in the euro, yen, pound and so forth, so that the foreign exchange rates between all the major currencies might not change that much. This is what happened during the last two major global currency decline events, in the 1970s and the 2001-2011 period. There was no refuge in any foreign currency.

For some people, this is a familiar idea. They have already been investing in development-stage junior gold mining companies, and stacking Silver Eagles, for years. But, for most people, it is a somewhat strange notion. Not exactly inconceivable, but not in their experience -- like having your hometown city invaded by a foreign military. We will have plenty of interesting stuff for the sophisticates going forward, but I want also to reach out to that much larger group of people who sense that maybe something is going on, and maybe they should do something, but are not sure what.

It is possible that the early stages of this process will drive stock prices much higher even than they are today. It is possible that things might eventually get so bad that the S&P500 goes to 20,000 (from 4200 today), while it loses 90% in real terms. We are not accustomed to the idea of having real values decline while nominal prices rise, but that is actually a common outcome in countries where currency values decline precipitously.

The results of this "currency decline event" are typically known as "inflation." Note the chain of causation: currency decline causes rising domestic prices, not the other way around. (Prices can also go up and down for nonmonetary reasons, such as growth, recession, shortage or glut.) This might be somewhat mild -- even so mild, as was the case in 2001-2011, that you could ignore it and still get by pretty well. But, I think the historical circumstances are lining up for something that hasn't been seen in America since the 1780s, when the Continental Dollar was hyperinflated into confetti. The legitimacy of the existing government, the Continental Congress, collapsed along with the value of its fiat paper. This led to the creation of a new republic, the United States of America, which intended to fix the problems of the old.

A coming hyperinflation:

This is a touchy subject because a lot of people have been warning about "hyperinflation" since about 2009, and nothing much has come of it, in the U.S., or even in places like Japan where potentially hyperinflationary factors seem to be even more acute. One reason the U.S. has been so successful since 1950 is that there has been enough virtue, within the political system, to avoid such outcomes that have plagued dozens of other countries in recent decades. One element of this collective "virtue" is those people who warn of the dangers of hyperinflation far ahead of time, perhaps when the actual risks are small, but still important. But, if we look at the past 300 years, we find that almost everywhere has had an experience of hyperinflation, including Russia, Germany, China, Japan, France, Italy, and the American Colonies. Nearly all of Latin America had hyperinflation in the 1980s, and nearly all of Eastern Europe had hyperinflation in the 1990s. Over 70 countries have had hyperinflation since 1950. Six countries had hyperinflation in 2020, including Argentina and Venezuela. It happens all the time.

I am using the H-Word today, not because it is a sure thing (it isn’t), but because Americans should at least have some idea of what hyperinflation is, and where it comes from. Mexicans and Argentines have learned this from hard experience, but it is a mystery to the typical American. Often, it isn't really the "price of a cup of coffee rises while you are drinking it" kind of event. These stories are amusing, but not very instructive. It might be around a 50%-per-year rise in the Consumer Price Index, which is only a few percent a month, over a number of years. There is actually a definition of "hyperinflation" from the International Accounting Standards Board, which has also been adopted by the U.S.'s Financial and Accounting Standards Board. It is basically: a 100% rise in the CPI over three years. That is only 27% per year compounded. About 2% per month. It probably doesn't seem very "hyper-." It produces strange oxymorons like "a mild hyperinflation." But, this standard arises from the experience of real companies, such as multinationals like Coca-Cola, or McDonalds, which have run real businesses in countries with hyperinflation. It is about the point where normal market processes, like accounting, break down. Concepts like expenses, depreciation, book value or profit become mysteries when the currency changes value rapidly. Accounting Standards appropriate for normal times can't be applied. This derangement of the basic internal functions of business are reflected in a breakdown throughout society. Things break. It gets ugly fast.

One characteristic of the “inflation” of the 1970s was that things didn’t break. It got close toward the end, in 1979-1980. But, Paul Volcker, Ronald Reagan and others stepped in to stop that runaway train. Thank goodness.

Basically, a hyperinflation (or a milder form of monetary inflation) is the same as a decline in currency value. This decline in currency value is apparent in the foreign exchange market, for example. It is not "relative to the CPI," or in terms of "purchasing power," or any such thing, although those are the inevitable consequences. If we take gold as a good measure of "stable real value," which I think is valid, then we would see the decline in currency value in the form of the value of a currency vs. gold. You can think of it as a sort of currency exchange rate, between "fiat money" and "old-fashioned money."

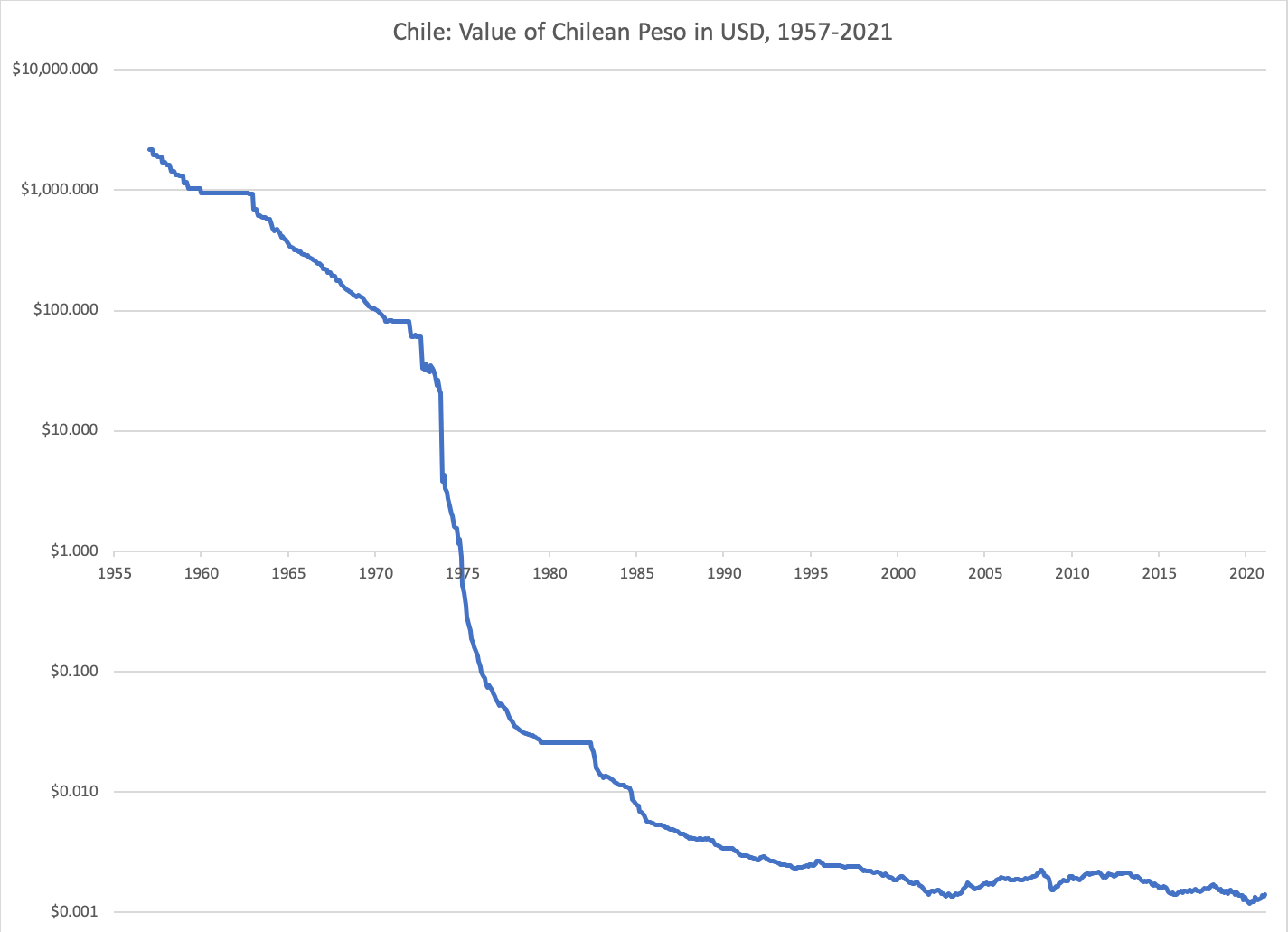

Here is an example from Chile, which had hyperinflation in the 1970s and 1980s.

Here’s the official CPI.

Here we will zoom into the 1980s-present:

First, the currency falls in value (here, expressed as the exchange rate with USD); then, prices rise in response. It’s no more complicated than that.

A currency can collapse in value even if the supply of currency doesn't change much. Actually, this is quite common. A currency can fall to 1/3rd of its prior value, even when the amount of currency is unchanged. But, if the amount of currency doesn't change, and there are not extreme external factors such as military invasion, usually the currency then stabilizes and may even regain much of its prior losses. This can be very unpleasant, but it is not hyperinflation.

The core element that causes hyperinflation is that the government is printing money to pay its bills. This is what causes the supply of currency to eventually increase enormously, and its value to asymptotically approach zero. For a long time, people thought that this was so obviously a bad thing to do, that only the sorriest governments would even consider it. But, the United States, and the whole world, is slipping into this habit. It can quickly become irreversible. When a government starts behaving badly like this, pretty soon it is no longer able to find customers for its regular government debt. There is a "loss of confidence;" or a "loss of faith." (The government inevitably blames "speculators" for this.) This not only includes debt issued to finance current deficits, but also, debt issued to refinance maturing debt. Europe's governments nearly got into a lot of trouble in 2012 when bond markets threw up on weaker issuers including the governments of Spain and Italy. So, it is not just a hypothetical fairy tale, but something that has recently happened to developed-world governments. The European Central Bank had to step in to prevent a disaster in 2012, exceeding its prior noninterventionist mandate to do so. It has been luxuriantly interventionist ever since.

A government that gets shut off from the bond market (at least, at acceptable prices and yields) faces some hard decisions. It might have to eliminate the deficit, by slashing spending by huge amounts. Just imagine if the U.S. Federal government had to slash its spending by perhaps 30% on short notice of a couple weeks. Existing debt, which can't be rolled over into new debt when it matures, might have to be "restructured" into longer-maturity debt. This is a form of debt default. One day, the government would simply tell bondholders that their 90-day Treasury Bills have become 10-year bonds. (Note: They don't give advance warning of when they are going to do this.)

You can imagine how unpleasant all this would be. It is so much easier just to use central bank money creation to "print the money." Think about that day. The Federal government has to spend hundreds of billions of dollars every month on all its programs and commitments. Is the Treasury just going to tell Social Security and Medicare recipients, or retired Federal employees, or bondholders, or the military, "Sorry, no more money for you"? Japanese finance minister Takahashi Korekiyo tried to tell the military that in 1936, and the military killed him. Yes, everyone in the room would know that they really shouldn't print the money. It is like putting a heroin needle in your arm. Everybody knows you aren't supposed to do that. But, they would anyway.

As inflation intensifies, tax revenues collapse, in real terms. We are liable for our taxes for the full year on April 15. We can easily extend to September. But, between today and September of next year, the value of the currency could fall a lot. $100 today is worth $10 in September of next year. Perhaps monthly tax withholding would keep revenues up, but wages typically also collapse in real terms. There is less to tax. Now, the government not only has to cover its prior deficits with the printing press, but also, the deficits get bigger since tax revenue is imploding.

The hyperinflation interacts with the tax code. As nominal incomes rise, high rates intended for millionaires are felt by the middle class, and eventually, by everyone including the lower incomes. The economy is crushed by the higher taxes, but the government does nothing, considering the higher tax rates an unexpected benefit since its tax revenues have collapsed. People disappear into the black market to avoid taxation.

If things get very serious, something counterintuitive happens: In a hyperinflation, nobody has any money. Yes, there are wheelbarrows full of banknotes, but they are worthless. Everyone learns quickly that they want to spend all the cash they have as soon as possible. The result is that nobody has any cash, in the form of banknotes, or bank accounts or money market funds, or anything of that sort. This is true of individuals, but also corporations and the government itself. This creates an acute need for cash, every day, because everyone spent all the money they had, yesterday. The government has to print money every day just to get through the next 24 hours.

Funny things happen to the political system when governments start printing money. People start to make up ridiculous rationalizations. The prospect of money for nothing is too great a temptation, and any sort of babble which tends toward that goal becomes widely accepted.

Example from France: Fiat Money Inflation In France, by Andrew Dickson White, was written in the 1890s about the events of the 1790s. (Click on the link for a free .pdf download from Mises.org.) Let's see how things were, in Paris in 1790, and if there was any similarity to today:

Early in the year 1789 the French nation found itself in deep financial embarrassment: there was a heavy debt and a serious deficit. The vast reforms of that period, though a lasting blessing politically, were a temporary evil financially. There was a general want of confidence in business circles; capital had shown its proverbial timidity by retiring out of sight as far as possible; throughout the land was stagnation. Statesmanlike measures, careful watching and wise management would, doubtless, have ere long led to a return of confidence, a reappearance of money and a resumption of business; but these involved patience and self-denial, and, thus far in human history, these are the rarest products of political wisdom. Few nations have ever been able to exercise these virtues; and France was not then one of these few. ...

It would be a great mistake to suppose that the statesmen of France, or the French people, were ignorant of the dangers in issuing irredeemable paper money; No matter how skillfully the bright side of such a currency was exhibited, all thoughtful men in France remembered its dark side. They knew too well, from that ruinous experience, seventy years before, in John Law's time, the difficulties and dangers of a currency not well based and controlled. They had then learned how easy it is to issue it; how difficult it is to check its overissue; how seductively it leads to the absorption of the means of the workingmen and men of small fortunes; how heavily it falls on all those living on fixed incomes, salaries or wages; how securely it creates on the ruins of the prosperity of all men of meagre means a class of debauched speculators, the most injurious class that a nation can harbor,—more injurious, indeed, than professional criminals whom the law recognizes and can throttle; how it stimulates overproduction at first and leaves every industry flaccid afterward; how it breaks down thrift and develops political and social immorality. All this France had been thoroughly taught by experience. ...

The first result of this issue [of new currency] was apparently all that the most sanguine could desire: the treasury was at once greatly relieved; a portion of the public debt was paid; creditors were encouraged; credit revived; ordinary expenses were met, and, a considerable part of this paper money having thus been passed from the government into the hands of the people, trade increased and all difficulties seemed to vanish. The anxieties of Necker, the prophecies of Maury and Cazalès seemed proven utterly futile. And, indeed, it is quite possible that, if the national authorities had stopped with this issue, few of the financial evils which afterwards arose would have been severely felt ...

France was now fully committed to a policy of inflation; and, if there had been any question of this before, all doubts were removed now by various acts very significant as showing the exceeding difficulty of stopping a nation once in the full tide of a depreciating currency. The National Assembly had from the first shown an amazing liberality to all sorts of enterprises, wise or foolish, which were urged "for the good of the people." ...

Even worse than this was the breaking down of the morals of the country at large, resulting from the sudden building up of ostentatious wealth in a few large cities, and from the gambling, speculative spirit spreading from these to the small towns and rural districts. From this was developed an even more disgraceful result — the decay of a true sense of national good faith. The patriotism which the fear of the absolute monarchy, the machinations of the court party, the menaces of the army and the threats of all monarchical Europe had been unable to shake was gradually disintegrated by this same speculative, stock-jobbing habit fostered by the superabundant currency. ... [T]here appeared, as another outgrowth of this disease, what has always been seen under similar circumstances. It is a result of previous, and a cause of future evils. This outgrowth was a vast debtor class in the nation, directly interested in the depreciation of the currency in which they were to pay their debts. ... This body of debtors soon saw, of course, that their interest was to depreciate the currency in which their debts were to be paid; and these were speedily joined by a far more influential class;—by that class whose speculative tendencies had been stimulated by the abundance of paper money.

I apologize for the very long quotes, but they are so delicious that it is hard to stop. The currency was eventually hyperinflated into oblivion in 1795, amidst the tumbling heads of aristocrats and kings. In the chaos and anarchy that resulted, Napoleon Bonaparte, a general at the head of an army in Egypt, overthrew the government in Paris in 1799. In 1800, he established the Bank of France, which relinked the franc to gold and maintained it unchanged until 1914. In 1804 Napoleon became Emperor of France, to popular acclaim.

Example from Germany: Rudolf Havenstein presided at Germany's central bank, the Reichsbank, during the 1919-1923 hyperinflation in Germany. He had ascended to the highest position at the Bank in 1908, and was there six years, until 1914, during which the gold-linked German mark was considered one of the best currencies in the world, and a major international "reserve currency." In the middle of the hyperinflation, however, he became an insane money-printer, pushing the printing facilities to their physical limits of banknote production, all the while claiming that this had nothing to do with the decline in the exchange value of the mark. When Money Dies (1975), by Adam Fergusson, describes what it was like at that time:

Hugo Stinnes himself, the richest and most powerful industrialist in Germany, whose empire of over one-sixth of the country's industry had been largely built on the advantageous foundation of an inflationary economy, paraded a social conscience shamelessly. He justified inflation as the means of guaranteeing full employment, not as something desirable but simply as the only course open to a benevolent government. It was, he maintained, the only way whereby the life of the people could be sustained.

The President of the Reichsbank whose industrial interests were negligible did not in essence depart from this argument, and in a speech on German currency in May 1922 greatly vexed [British ambassador] Lord D'Abernon because he had (in the ambassador's words) 'pressed into the shortest space the maximum number of fallacies and errors'. As though his powers to wreck the economy were not great enough already, at the behest of the Reparations Commission, and in the expectation that money supply would thereby be divorced from political expedience, the Reichsbank was that same month declared autonomous, with Dr. Havenstein its uncrowned king. He quickly showed that he, too, considered the fall in the exchange [foreign exchange rate with gold-linked dollars] to be quite unconnected with the gigantic increases in note issue, and went on 'merrily turn[ing] the handle of the printing press completely unconscious of its disastrous effect'. There was evidence, D'Abernon believed, that 90 bankers in Germany out of every 100 expressed and perhaps held the same views. At any event, the financial press reported them without dissent.

By May 1922, there could be no mistaking the consequences of the continuing issuance of currency. That month, a Cost of Living Index was 232% higher than a year earlier. But, the largest industrialists, the banking industry, and the central bank head -- every one of them serious and studious people -- mostly claimed that what was obviously happening was not really happening. In 1922, the government's tax revenue had fallen to the equivalent of 1,488 million prewar gold marks, from 2,927 million the year earlier. The government spent the equivalent of 3,950 million gold marks. 63% of total government spending was financed by the printing press, and they weren't ready (yet) to switch off 63% of the government overnight. This was the reality behind all these gloriously inane public statements.

Today, we have "Modern Monetary Theory," an open-ended excuse for the government to print money for whatever it might like to spend money on, which will doubtless be very popular until it is not. Its chief proponent is economist Stephanie Kelton, explaining why the U.S. government doesn’t need to take money from one place (taxes, bond investors) to spend it somewhere else. It doesn’t need to “find the money.” It can just spend.

Kelton has been included on the Politico 50, the Bloomberg 50, and World’s Top 50 lists of most influential people today. She was the Chief Economist for the Democratic Minority Staff of the Senate Budget Committee, before becoming an economic advisor to Bernie Sanders. We have always had people like this on the sidelines (just as there were 200 years ago too), but from time to time, they are lifted to the forefront, when they are delivering the message that everyone wants to hear. It doesn’t really make sense, but people wished it did, and that’s enough for them.

Although not yet officially embraced, “Modern Monetary Theory” lies behind the deluge of new spending proposals coming from the Democratic Party, including the latest $1.8 trillion "American Families Plan," (preschool) not to be confused with the $2.3 trillion "American Jobs Plan" (bridges) from last month, or the $1.9 billion "American Rescue Plan Act of 2021" (cash payments and unemployment benefits) signed into law in March, or the $900 billion rolled into the "Consolidated Appropriations Act" and passed in December. (Why Congress feels the need to keep identifying which country this is, I don't know.)

As I mentioned, the core element of a hyperinflation is printing money to fund the government. Before 1971, the U.S. and most of the world used the Gold Standard, in its Bretton Woods incarnation. The U.S. dollar's value was linked to gold at $35/oz. Since 1971, we have had floating fiat currencies. During these 50 years, there have been two major currency decline events, in 1970-1980 and in 2001-2011. These two events account for why it now takes $1800 to buy an ounce of gold today, compared to $35 in 1970. But, in those two prior periods, debts and deficits were not really an issue. The U.S.'s debt/GDP ratio was low in the 1970s, and deficits were small. Interest rates soared to double-digit levels, but this was not such a big deal because the Federal Government's debt held by the public/GDP ratio was only about 27% in 1970 and 24% in 1980.

The base money supply in the U.S. grew during the 1970s, but it did not grow very much -- actually, the growth rate was almost the same as the prosperous 1960s, and the prosperous 1980s. It was not a case of “printing money to fund the government.”

Today, with Federal debt held by the public around 100% of GDP, if the Federal government had to pay a mere 6% on this debt (common in the 1990s), that would mean 6% of GDP in interest costs alone, or about a third of total Federal tax revenue. Plus, all the existing deficits from legacy programs, and all the new commitments that the Democrats have piled on just since November 2020.

Debt and deficits, and the money-printing response, weren't really a factor in the 1970s, and (arguably) in the 2001-2011 period. Today, they are a big deal, not only in the U.S., but throughout the developed world.

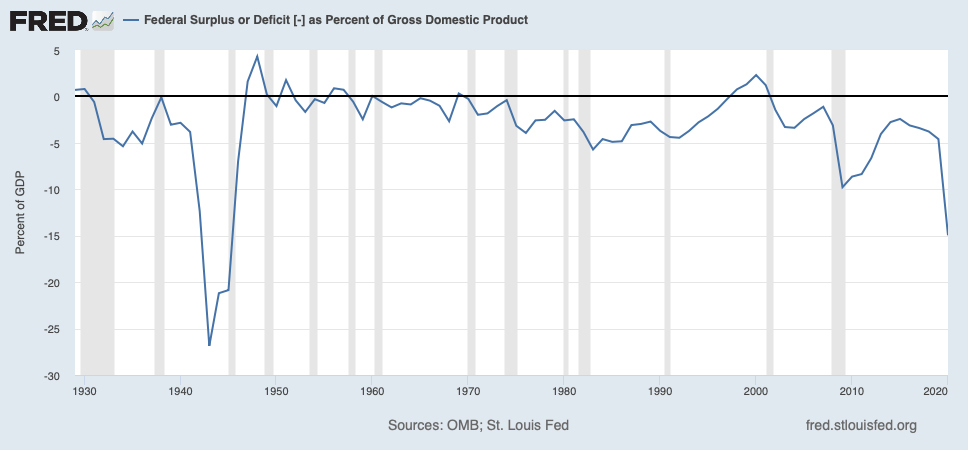

In 2020, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet expanded by $3.2 trillion. In essence, it “printed” $3.2 trillion dollars. Federal Debt held by the public increased by $4.2 trillion. The official budget deficit for FY20 (ended September 2020) was $3.1 trillion. That was a deficit of 14.9% of GDP. So, we see that the Federal Reserve essentially “printed money” equivalent to the deficit, which was the largest deficit since World War II. (Much of this excess cash ended up in the Treasury Department’s own checking account, where it lay quietly. But, that dormant cash from 2020 is now being injected into the economy in 2021.)

Probably, you are wondering: Why has all the money-printing since 2009 not had much effect? I think there are good reasons for this, which I will explain later. Basically, we needed a lot more money, because we imposed new regulations on banks that required them to hold a lot more cash. These were the Basel III requirements, passed in 2010 with full phase-in in 2019. This cash didn’t exist, so it had to be created. Banks didn’t really meet their Basel III requirements until 2020. There was actually a shortage of bank cash at the end of 2019. But, now that demand for cash seems to have been satisfied, at exactly the moment when the political system seems to have become addicted to printing-press finance.

In 2021, the Treasury says that it will spend about $1.4 trillion of the cash that it built up in 2020. Plus, the Federal Reserve says that it will “print money” and buy bonds at a rate of $120 billion a month, probably for the rest of the year, or $1.44 trillion per year. That is a combined $2.84 trillion (about 13.5% of GDP) that Congress can spend without “finding the money.” Every penny of it came from the “printing press” (Federal Reserve base money expansion). Can you see why they are going nuts with spending in Congress? The projected deficit for FY21 (October 2020 to September 2021) is now at $3.46 trillion (15.7% of GDP), according to the Congressional Budget Office, just counting what has already been passed into law — not the $4.1 trillion (over ten years) of add-ons listed above.

What to do:

The point of all this is not to tell scary ghost stories around a campfire, but to recognize that the risk of significant monetary decline, and even hyperinflation, is real. We are not predicting the future so much as exercising our minds, considering the potentials, and taking appropriate precautions. We need to consider the possibility, which, evidently, All the Investors have not taken seriously yet. For our investing portfolio, this means that our portfolio should be able to withstand the onset of a hyperinflationary event -- and also, be relatively sound if that doesn't happen. We don't have to "bet it all on black," but neither should we "bet it all on red" (stocks and bonds). Nobody is going to wave a flag and say "it's hyperinflation time now!" That comes mostly from historical hindsight. Maybe, in the future, historians will say that it has already begun.

Even if things never get to a hyperinflationary stage, there still may be significant monetary inflation, as in the 1970s. Or, maybe, nothing much happens at all, as has been the case in Japan for the last few years. Being wrong and making money anyway is a wonderful way to be wrong.

Imagine your portfolio, in the event of a serious hyperinflation. Not a Weimar Germany or Zimbabwe "billion-dollar banknote" hyperinflation, but a 100:1 decline in currency value over the course of ten years, as was so common in Latin America in the 1980s. Basically, the bonds and the cash would lose 99%, and the stocks would probably lose about 90% (or, rise 10x in nominal terms). If you have a typical 60%/40% stocks/bonds portfolio, it would emerge, after ten years, worth about 6% of its initial value. If you “rebalanced” along the way, taking bonds/cash back up to 40% periodically, then the total losses would be a lot more than that. But, I think people would learn not to do that pretty quickly.

If you took 10% of the portfolio from the bonds/cash section, and put it in gold bullion, you would have 16% of the original value after ten years (10% gold plus 6% stocks), which is almost three times better. Over the past three centuries, the value of fiat paper currencies, separated from their traditional metallic anchors, has tended toward zero. This process might be gradual, or sudden. Today's dollar is worth only about 1/50th of what it was worth during the Kennedy Administration, compared to gold (which probably hasn't changed much). That is a big decline. In the future, there will be more declines; we simply do not know the timing or magnitude. Studies by the World Gold Council found that, since 1970 -- in other words, during the floating fiat era -- having a 10% allocation to gold bullion produced better results and uncorrelated returns compared to a traditional 60%:40%-type stock and bond portfolio. Based on this, we see people like Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates (one of the most successful macro hedge funds of all time), or newsletter writer Jim Rickards (who wrote several popular books about currency decline that I thought were credible), recommending a similar 10% allocation. Nothing very bad can come of it, but it might be a big help if things get serious. If a professional advisor recommended it, and it underperformed for some length of time, they might not lose their job. Maybe.

However, at this time I would go with a larger allocation than this, either to gold itself, or a variety of Hard Assets that would likely do well for the same reasons. This violates all the principles of Career Risk. No professional advisor can say this, and expect to keep his job. You will have to take things into your own hands.

Gold is Money: Recently, as stock prices rise, big pension funds have been trending toward fixed income/cash. This is a rational response to very high equity valuations, but an irrational response to rising monetary risks. That stuff can go to zero, or nearly so. Some of that "cash" allocation should be toward non-devaluable forms of cash, which traditionally means precious metals, specifically gold. The basic characteristic of gold, as an investible asset, is that its real value doesn’t change much. This is what people mean when they say that “gold is money.” Gold is rarely used in a monetary way today, but it was the basis of monetary systems around the world for thousands of years, until 1971, because it has the most desirable characteristic of money: Stable Value. When you are looking at the “price of gold,” think of it as a foreign exchange rate between New Money and Old-Fashioned Money. Since we know that today’s floating fiat currencies go up and down in value, that means if gold is mostly stable in value, then most of the change in “gold prices” is due to the change in the floating fiat currency, not gold. There is some disagreement about the extent to which this principle is really true. However (as someone who has written three books about the gold standard, which deal with this topic in depth), I can say that: I think it is mostly true.

An asset whose main characteristic is that it doesn’t go up in value, and also does not produce any current cashflow, does not seem like much of an investment. It is useful primarily in these currency decline events, when, due to the decline in value of the currency itself, the real values of nearly everything else falls, sometimes a lot. In those times, something that is inert and unchanging, or as they say, “like a rock,” is exactly what you want.

This allocation could be in the form of bullion, and alternative precious metals including silver and platinum (both of which I favor at this time). Some could be in the form of gold mining equities, specifically gold mining royalty companies like Franco Nevada, Royal Gold and Sandstorm Gold, which have an unusually attractive combination of moderate gold-like volatility, with cashflow yield and strong growth characteristics. If you were to take a somewhat agnostic, "who-the-heck-knows-what-will-happen?" approach, it might lead to evenly dividing a fixed income/cash allocation, with half in precious metals and half in fiat currencies. One of them will work out. In this case, 50% becomes 25%:25%. If some of these things I am talking about happen, even in a mild way, you are going to think that a 25% allocation to gold or other hard assets was way too little.

I think everyone should have at least a little bit of gold bullion directly owned, even if just for the principle of the thing. A handful of coins hidden somewhere in the house, perhaps. For some reason, people are uncomfortable about this, while gladly buying the most dubious and speculative assets around, including Dogecoin or the Ark Innovation ETF (ARKK). Time to get over it. I especially recommend a generic $20 Saint-Gaudens gold coin from the 1920s -- not collectible "mint state" coins, although those are also attractive at this time. Find out what "a dollar" was, in the 1920s. To this, you might add some quarter-dollar coins from the early 1960s, made of 90% silver. Wow.

Before we are done, in perhaps 5-8 years, today's U.S. coinage may disappear — even setting aside the possibility of “central bank digital currencies,” which I think will be rolled out over the same timeframe. Already, the U.S. penny and nickel are worth more melted down for their base metals. When it was introduced in 1871, the Japanese Yen was worth one U.S. dollar. Subdivisions of the yen were known as "sen" (1/100 of a yen) and "rin" (1/1000 of a yen). No "sen" or "rin" coins exist today, a consequence of hyperinflation in Japan in the late 1940s. Even the one-yen coin had been abandoned by the 1980s, with the copper 10-yen coin the smallest denomination, and all retail prices rounded to the nearest ten yen. Today’s laughably lightweight stamped aluminum one-yen coin was introduced in the early 1990s, as it became necessary to make small change after the introduction of a 3% national sales tax in 1989.

Right now, there is a shortage of physical gold and silver in retail size (instead of large bars). Pricing premiums are high. It is a good time to focus mostly on securitized options, perhaps rolling into physical bullion later if you choose to.

Among securitized options, I prefer the Sprott Physical Gold Trust (PHYS) to other offerings including GLD. As it is technically a closed-end fund rather than an ETF, PHYS tends to vary a little more from its NAV than other ETFs. Mostly, this is toward a discount, which is nice if you are buying, but not if you are selling. Sprott also has an offering for silver, the Sprott Physical Silver Trust (PSLV), which has sometimes had larger discounts to NAV. I prefer it among listed silver-linked ETFs and CEFs. There's even an ETF for platinum, the Aberdeen Standard Physical Platinum Shares ETF (PPLT), and a Platinum/Palladium fund also from Sprott (SPPP). Platinum is very cheap vs. gold these days, and also compared to palladium (its competitor for use in catalytic convertors for automobiles), but that valuation gap has begun to close. The Van Eck Gold Miners ETF (GDX) is a nice way to get exposure to the gold miners, which have been making a lot of cashflow recently. It doesn't have to be any more complicated than that. A really good manager of exploration and development-stage junior mining companies is likely to do very well, but they are hard to find. Casey Research (caseyresearch.com) focuses on this sector, but it can be a dangerous place for neophytes. Unless you can give it full-time commitment, you are probably better off looking for a specialist.

Gold prices have come down after a big rise in 2020, while nearly all other commodities have soared higher. I think it is time to “buy the dip.” Perhaps later, other commodities including copper, iron ore and wheat, which have been on a nonstop roar higher in recent months -- the biggest, fastest rise since 1973 -- will have a correction just as gold has had, giving us a nice buying opportunity in these other Hard Assets.